The following is a recording and transcript of Ibram X. Kendi’s remarks at the symposium "Mascots, Myths, Monuments and Memory" on March 3, 2018. Kendi is a professor of history and international relations at the American University (AU) in Washington, D.C. as well as the director of The Antiracist Research & Policy Center at AU. For more information on the symposium, see this op-ed on the discussion from the Museum's Founding Director Lonnie G. Bunch III.

The title of my brief talk is the unloaded guns of racial violence. The unloaded guns of racial violence.

I grew up in Jamaica Queens, New York.

That’s in the south side of Queens—a majority black area.

And when I was in high school, my parents decided to uproot, literally, my brother and I from Jamaica, Queens, and we moved not far from here to Manassas, Virginia. This is after my freshman year in high school.

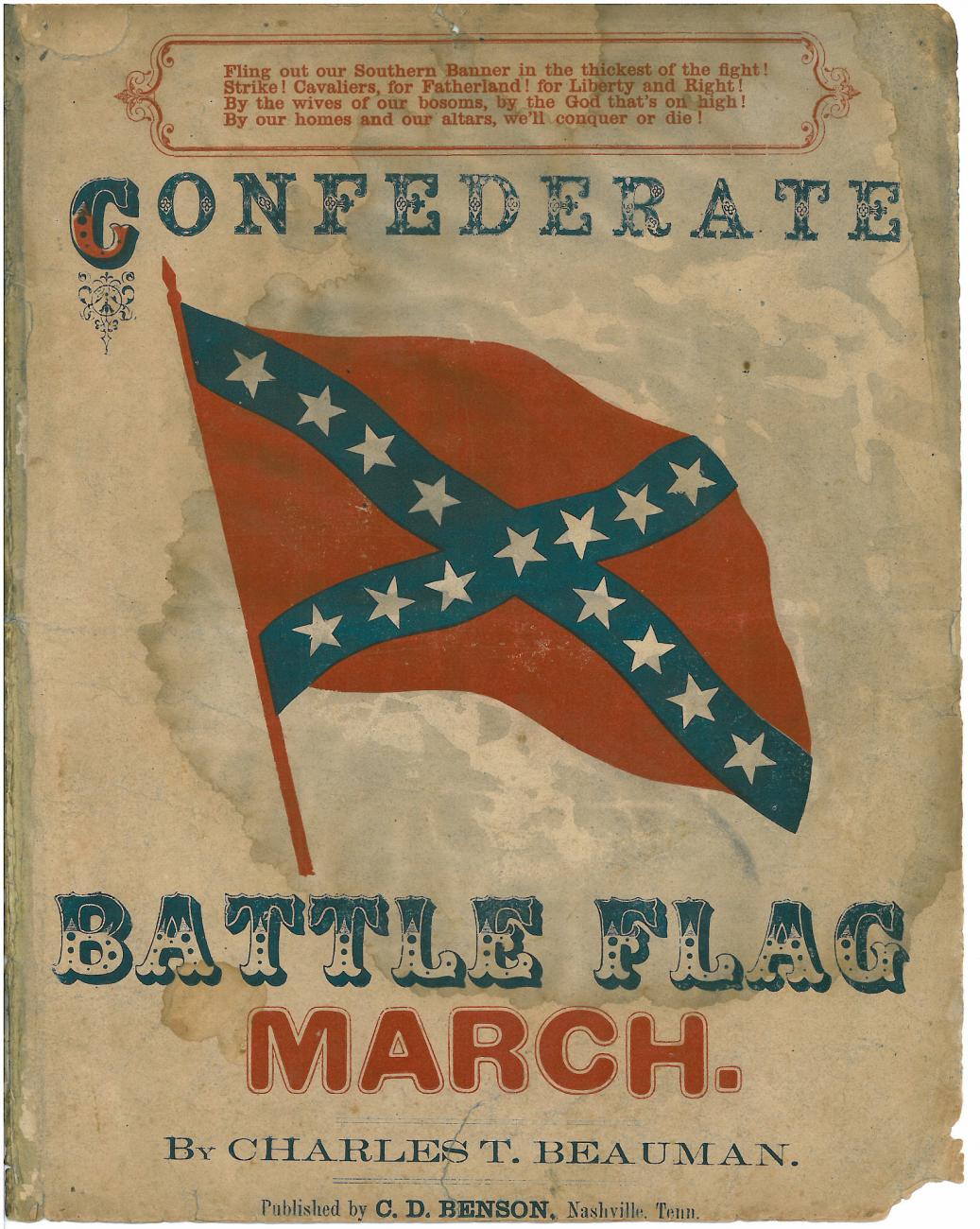

Little did I know that armed Confederate memorials would be surrounding me like Robert E. Lee’s army.

Little did I know that in Manassas I would be surrounded by fans of Washington DC’s football team, wearing the image of the mascot every chance they got.

Little did I know that tourists would be trekking continuously up to Manassas National Battlefield Park to literally relive the confederate victories at the first and second Battles of Bull Run during the Civil War in 1861 and 1862.

My family actually often shopped at Bull Run Plaza up the street from our home. My brother literally worked at a grocery store at that plaza. I worked out at a gym at Bull Run Plaza. Even our favorite pizza shop was in that plaza.

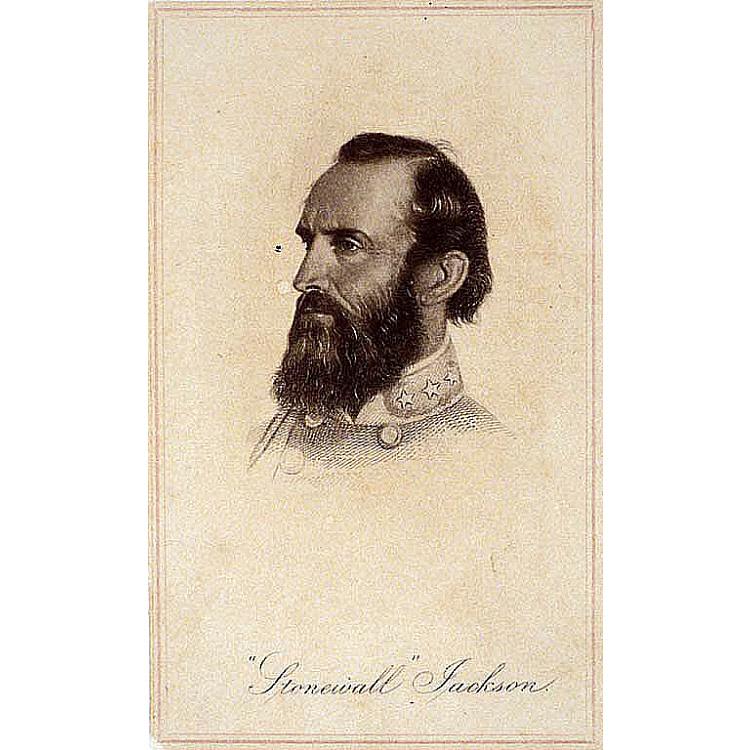

My parents enrolled me in the nearby high school in Manassas named Stonewall Jackson High School.

It was at these successful battles of Bull Run that Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson acquired his nickname Stone Wall.

It was there that northern Virginians kept the stone wall intact. After all of these years, my high school is named after, and thereby honoring a man who accepted the almighty enslavement of my ancestors.

Of you, of me, as sanctioned by almighty God.

Honoring a man who battled, literally, to preserve the slaveholding lives of my ancestors.

When I learned who Stonewall Jackson was, when I learned the significance of the Battles of Bull Run, when I realized why tourists continued to trek up to this Battlefield Park near my home, literally clothed in confederate flags, I started to feel as a high school student, and even as a college student, unsettled.

I started to feel unsettled like when people who despise my existence walk around me with unloaded guns.

I knew their guns, these guns, could not, would not kill me but my historical memory of how many people like me those guns had killed sapped my comfort, injected me with anxiety—anxiety that sometimes went away, but other times, if not most times, turned into fear. Fear of racial violence.

In thinking through my comments for today, I tried to really understand, first and foremost, how it felt for me, how it feels for so many of us to live day in and day out surrounded by so many confederate monuments.

How does it feel for those people that have to literally watch people cheer for mascots that are a desecration of their people?

How does it feel to see myths memorialized in public squares, in massive stadiums?

And more importantly, what do these feelings say about our memories and our histories, let alone the memories of the defenders of these monuments and mascots?

How can we use these feelings and memories as a motivation to never stop digging into American history to uncover the graves of racial violence?

And how can we study these graves, the dead, to give us a better sense of the living—the life of racial violence in the United States today?

These are the questions that led me to this construction of the unloaded gun of racial violence. That seems to be always pointing at black people and their indigenous sisters and brothers from that nearby park and building and square and field and wardrobe and television screen.

And this is not to be confused with the loaded guns of racial violence being deployed and defended by badged and unbadged white supremacists.

In thinking through this unloaded gun of racial violence, that the monument, that the mascot appears to be, I wanted to also think through the historical function of this unloaded gun.

What is it literally attempting to do throughout history? What is it attempting to do today?

In writing Stamped from the Beginning, a long history of anti-Black racist ideas, in speaking about this book, I have spent most of my time expressing the relationship between racist ideas and racist policies.

The popular idea that the causal relationship of ignorance and hate leading to racist ideas, in other words, those who have produced racist ideas about black people, produce them because they were ignorant and hateful and that those people who had those racist ideas are the people who were behind racist policies from slavery to mass incarceration. That popular, causal link that we have long been taught I found was ahistorical and actually it’s been quite the opposite.

Powerful people have instituted racist policies, typically out of cultural, political, and economic self-interest, and those policies then led to the creation of racist ideas to defend those policies, to make you and I believe that the effects of those policies, which are consistently racial disparities and inequities, are not the cause of those policies, but are the cause of black inferiority, so that we can then spend our time thinking that the problem is people as opposed to policy and then they can continue to benefit from those policies. And then people consume these racist ideas and that is how they became ignorant and hateful. That is what I write about and show in Stamped from the Beginning, showing that the relationship is not racist ideas leading to racist policies but racist policies leading to racist ideas.

But another storyline in Stamped from the Beginning that I don’t really talk about as much that I would like to talk about today is the relationship racist policies and racist ideas and racial violence.

That’s a relationship that I don’t necessarily talk about, but I think it’s crucial for us to understand the role, the function, that racial violence plays.

And it reminds me of something that happened in this country not far from here at the beginning of the 20th century. On October 16, 1901, the newly sworn in President Theodore Roosevelt, hearing that Booker T. Washington was in town, had him over to his house for family supper. Roosevelt did not think much of this invite, failing to size up the mood in 1901 of segregationists, the mood of so many Americans—Americans whose decades of voter suppression, laws, and racial violence had finally succeeded in removing the last black politician from Congress in January 1901.

Americans who were learning from scholars from Columbia University’s well respected Dunning School that during the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War, that the white south had been victimized by corrupt and incompetent black politicians.

“All the forces that made for civilization were dominated by a mass of barbarous freedmen,” wrote the school’s dean William Archibald Dunning.

Americans like novelist Thomas Dixon, who in 1901 was writing his Reconstruction Trilogy, that “to teach the north what it has never known, the awful suffering of the white man during the Reconstruction period and to demonstrate to the world that the white man must, and shall be supreme.”

Americans like the Daughters of the Confederacy, one of the more influential organizations, energizing the largest ever wave of new Confederate monuments in the early 20th century. Monuments that sat on subjected bodies like the unloaded guns of Jim Crow.

Americans like William Hannibal Thomas, who wrote in his 1901 acclaimed book about a “black record of lawless existence led by every impulse and passion,” causing black people to call this black man the black Judas.

Americans like Mississippi Charles Carroll, who titled his bestseller the previous year The Mystery Solved:

The Negro a Beast. A soulless beast, prompting W. E. B. Du Bois to capture and present two years later

The Souls of Black Folk.

When Roosevelt’s press secretary casually notified Americans the next day of Booker T. Washington’s visit, the social and racist earthquake was immediate and loud.

Black Americans were largely beside themselves in glee and many fell in love with Theodore Roosevelt. Now that love didn’t last, but to segregationists, Roosevelt had literally crossed the color line.

“When Mr. Roosevelt sits down to dinner with a Negro, he declares that the Negro is the social equal of the white man,” stammered a restrained New Orleans newspaper.

But South Carolina Senator Ben Pitchfork Tillman was not restrained. “The action of President Roosevelt in entertaining that nigger will necessitate our killing a thousand niggers in the south before they will learn their place again.” This is a U.S. Senator, Tillman, who was no stranger to racial violence.

In Hamburg, South Carolina, the local black militia celebrated the July 4 centennial in 1876 like people were across the country. Arian white racists hated the militia for maintaining black people’s local ability to control this majority black town.

During the parade, harsh words were exchanged while a local white farmer ordered militia members to move aside for his carriage. The farmer appealed to former Confederate General Matthew C. Butler, the area’s most powerful democrat. On July 8, Butler and a small posse ordered the militia head union army veteran Doc Adams to disarm the Hamburg militia. Adams refused and fighting broke out. The militiamen retreated to their armory. Butler dashed off to nearby Augusta, but returned with hundreds of reinforcements and canon, including Ben Pitchfork Tillman.

Butler’s contingent executed at least five black militiamen and looted and destroyed the undefended homes and shops of black Hamburg. Tillman had all year long been leading a para-military group of red shirts because this was an election year; the election year of 1776 when South Carolina’s white supremacists finally regained control of that state through their guns and stuffed ballot boxes.

When southerners complained of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, President Ulysses S. Grant realized they were complaining about their “lost freedom to kill Negroes and Republicans without fear of punishment and without loss of caste or reputations.”

General Butler made a mockery of the Congressional investigation of the Hamburg Massacre, capitalizing on the attention that was brought to him by being elected to the U.S. Senate in 1877. He blamed the massacre on innate black criminality.

“Blacks,” he said, “possess little regard for human life.”

It just reminds me of people today saying that black lives don’t matter and their response is that there is actually a war on cops.

Tillman also used his role in the massacre as a springboard into politics. He became the governor of South Carolina in 1890 and entered the U.S. Senate in 1895 until his death in 1918. He spoke continuously as a politician about this Hamburg Massacre as sort of a badge of honor. During the red shirts reunion in 1909, he said, “the purpose of our visit to Hamburg was to strike terror.” And the next morning, Sunday, when the Negroes who had fled to the swamp returned to the town the ghastly sight which met their gaze of seven dead Negroes lying stark and stiff certainly had its effect.

In 1916, South Carolina erected a monument in honor of 23-year-old Tom Merriweather, the only white man who died during the Hamburg Massacre.

Tom was a young hero, according to the monument’s inscription, who “died maintaining those civil and civic institutions which men and women of his race had struggled through the centuries to establish in South Carolina.”

By his death, he assured to the children of his beloved land the supremacy of that ideal.

I learned from Ben Pitchfork Tillman, of all people, the real purpose of racial violence historically. When racist ideas won’t subdue black people, racial violence is oftentimes next. And when the smoke from gunshots of racial violence clear, those subdued people must be shown these unloaded guns of racial violence all around them.

So we remember those gunshots. So the threat of racial violence stalks our every move like our shadows.

So those who adore Confederate monuments, those who cheer for the mascot, are effectively adoring and cheering for racial violence. That’s essentially what we are dealing with after all of these years, with so many people surrounded by so many monuments and so many mascots.

And I think when we reconsider or begin to think about the monument, the mascot as an unloaded gun of racial violence, we can also begin to connect it with the larger discussion that is happening right now over what? Gun control. Over removing guns, literally, from America, particularly assault weapons, particularly weapons that terrorize Americans.

And so I think when we think about the historical context of these monuments we can literally think about it in the context of fighting against guns because they literally have served that purpose throughout American history.

Now they are not loaded, right? They are not literally going to kill people, but I think everybody can understand the analogy of what an unloaded gun can do, and is doing, to people. Thank you.