Jazz history as we know it largely celebrates a handful of people, predominantly male musicians. However, without the contributions of female performance artists jazz might not have become the global movement that is today.

The traditional canon of jazz culture tells one story of the musical developments made by bandleaders, vocalists, and instrumentalists. However, jazz went far beyond just music. It also included elaborate stage productions with casts of multifaceted artists. Chorines, dancers, actors, and comediennes created a multisensory experience that drew major audiences to venues catering to mixed-race or segregated audiences. One group whose artistry has been diminished over time were chorines, sometimes referred to as chorus girls.

A bronze silhouette, a lovely dancing faun, etched in tan shading might serve to describe Laurie Cathrell, scintillating dancing star currently appearing at the Club Harlem in Kansas City. Earl J. Morris in “Laure Cathrell: As I Know Her” (November 1935)

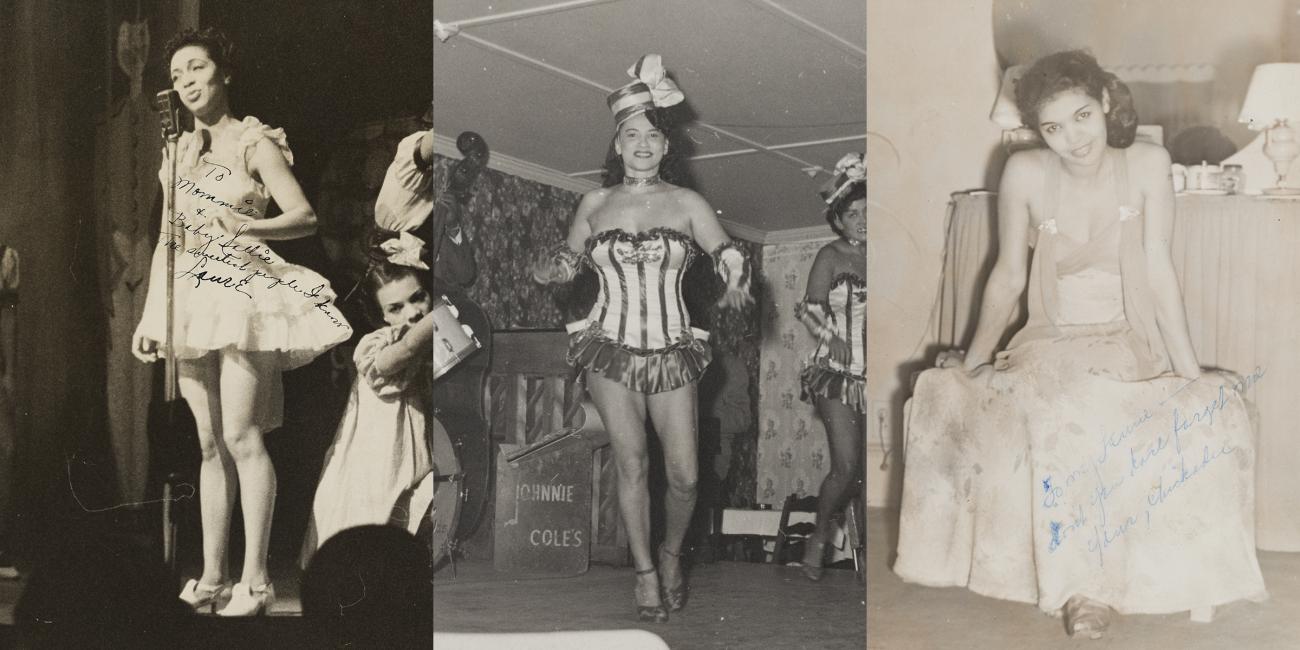

Surviving collections of photographs, correspondence, oral histories, and material belongings have gone a long way in uncovering the forgotten parts of jazz history. At the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), the Cathrell Collection presents not only a diverse picture of the jazz scene of the 1930s and 1940s, but also shines a spotlight on the careers of chorines whose high-energy performances have been overlooked. Through the journeys of three chorines represented in this collection, Laurie Cathrell (1914–1999), Birdie Warfield (ca. 1916–unknown), and Chickie Collins (ca. 1915–1942), one can see that chorines were not merely ornamentation for big bands, but talented, ambitious performers in their own rights. The collection illustrates the challenges unique to chorines, and particularly Black chorines, whose intersectionality put them in the center of complex social issues, such as colorism, racism, sexualization, and misogyny.

The story of these women begins beyond the bright lights of Harlem, in St. Louis, MO, another significant cultural capital of the United States. When Laurie, Birdie, and Chickie began their careers in the mid-1930s, the city was thriving. Black-and-tans—white-owned clubs catering to white audiences, featuring Black talent–boomed during Prohibition as speakeasies where alcohol could be consumed away from the watchful eyes of law enforcement. These venues were often run by, or affiliated with, crime syndicates that engaged in bootlegging or racketeering that frequently involved corrupt policemen and politicians. These clubs catered to a middle-class white community looking to imbibe and escape the dreadful state of the world with exciting spectacles featuring fast-paced swing bands, witty comedians, sensual dancers, and light-skinned chorines that all performed in roles reinforcing the racial hierarchies of the day.

Such was the place where Laurie, Birdie, and Chickie met in St. Louis’ Club Plantation, run by the Scarpelli Brothers. The club, modeled after Harlem’s famous Cotton Club and other successful Black-and-tans in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, opened its doors on August 25, 1932, and grew into a successful venture featuring the best Black talent the brothers could find. The club employed a line of chorines, known as the Plantation Dollies, that featured women who could dance, sing, act, engage in stage banter, and meet the very specific set of White-European beauty standards enforced by producers. This included humiliating and anti-Black practices like the “paper bag test.” This practice perpetuated the racist and sexist idea that dark-skinned Black women are not beautiful. However, being a chorine for all of its potentially degrading obstacles was an opportunity to escape the drudgery of domestic work. If a woman could tolerate the difficulties of working in a paternalistic entertainment industry, life on the road as a chorine allowed a select few women artists to live boldly, and to explore the world.

The owners of Club Plantation were Anthony “Big Tony” Scarpelli (1899–1978) and his older brother, James “Gentleman Jim” Scarpelli (1896–1981), both gangsters associated with the St. Louis mafia. Gentleman Jim was a silent partner in the club due to his extensive criminal record, which included robbery and gambling. Big Tony served as the public face, despite having his own criminal record that included public liquor law violations and a history of armed robbery. Tony hand-picked the talent that performed in his club and was known to travel to New York to scout additional bands and acts.

The Scarpelli brothers envisioned a band comprised of the best musicians they could bring to St. Louis. They eventually settled on the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra, who played as the club’s house band from 1934 until 1944. Over the course of their time at Club Plantation, the Orchestra gained a reputation as a training ground for younger musicians before they moved on to join New York City-based bands, including Count Basie and Duke Ellington’s orchestras. A few notable alumni of the band include trumpeter Harry “Sweets” Edison, guitarist Charlie Christian, and drummer Art Blakey. The band played a similar repertoire to other big bands, including popular swing tunes and new compositions. They were accompanied by a bevy of chorines and other entertainers.

Chorines were discovered in numerous ways, including recruitment from beauty contests, talent shows, or community performances. Such was the case with Laurie Cathrell who trained in ballet with Ms. Mildred Franklin from a young age and later got her big break as a teenager after winning a local “bathing beauty contest.” She parlayed her win into a position with the traveling dance company, “Shake Your Feet.” Chorines were chosen for their slender bodies and most significantly, their light skin. The deliberate hiring of light-skinned dancers promoted anti-Blackness and racial stereotypes painting Black women as seductresses. Light-skinned chorines were perceived as more attractive to white audiences, which fit into a long practice of reducing mixed-race Black women to “commodified racial desirability.” This desirability in Jazz Age entertainment determined by white hegemony fed into fantasies and fears of interracial socializing in jazz spaces.

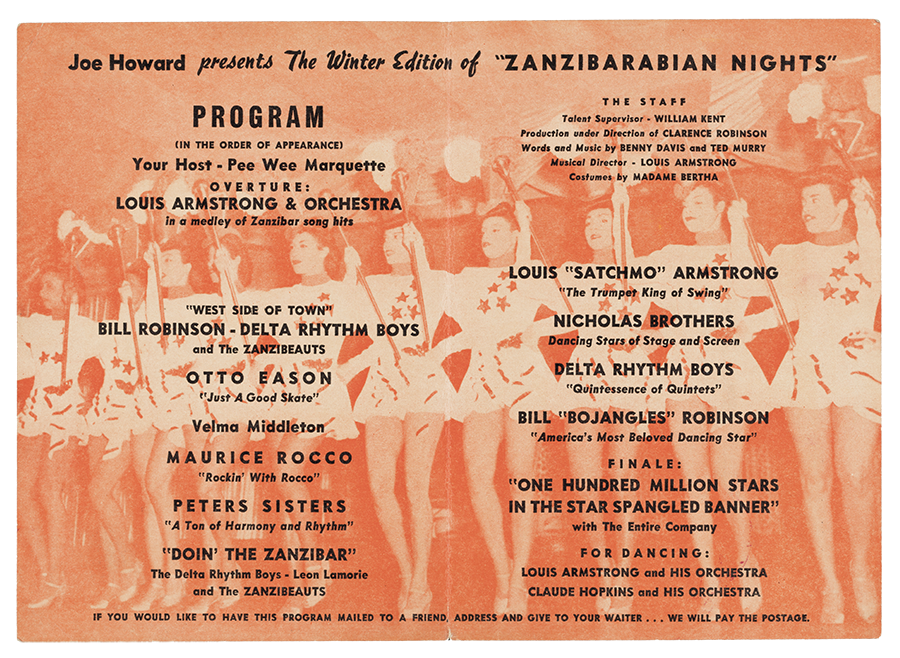

Show formats varied from club to club, but largely followed a format similar to vaudeville shows. An emcee would introduce the show, followed by an appearance by the house band and perhaps the house chorus line. As the program progressed, supporting acts would perform ballroom dances, short dramatic scenes, comedic routines, and energetic dances that built up momentum for the headlining acts and the grand finale. Chorines would perform throughout a program and also act in scenes.

At the time, chorines were also celebrated for presenting an inspiring example for Black women. In a 1928 Pittsburgh Courier article, Eva Jessye expressed her respect for chorines being “the most active medium in glorifying the Negro woman” by writing: “The chorus girl has forced recognition of the beauty and charm of the colored woman not only from the outside, but has awakened the Negro woman herself to her own possibilities, which feat may be considered the greater accomplishment.” However, light-skinned women’s inclusion came at the expense of darker-skinned Black women and perpetuated colorism. Compounding the issue further, the rise of chorines also coincided with the growth of Black beauty companies who frequently turned to models, chorines, and entertainers for their advertisement campaigns. Because of their position in entertainment and the media, chorines exemplified American ideals of beauty, desirability, and femininity that have sought to manage Blackness for centuries. The preference and celebration of these talented, light-skinned women as respectable models nationwide illustrates how racism can be internalized. It historically manifested within the Black community through beauty trends that included popular products, such as skin lightening creams and hair straighteners. Within the larger the context, this indicates the extent to which Black women are degraded or celebrated based on their image. All of this is significant, and deeply tied into the careers of Laurie, Chickie, and Birdie who were all light-skinned and svelte.

When Laurie left the traveling dance company to return to St. Louis in 1933, she was hired as a chorine in Club Plantation’s first revue. Birdie, who was also a Missouri native, began performing at Club Plantation the same year. While performing there, Birdie also met and began a relationship with her future husband, Harry “Sweets” Edison. Olive “Chickie” Fields also joined the chorus line in 1933. During her time in St. Louis, she married Claude Collins, a locally known performer for a St. Louis radio station, and took his name. For trained dancers such as Laurie, Birdie, and Chickie, venues like Club Plantation provided one of only a handful of opportunities for these young, female, Black artists to follow their dreams to professionally practice their craft.

However, there could also be significant social consequences for pursuing such a career. Peggy McCullin Smith, younger sister of Club Plantation dancer Vivian McCullin (a contemporary of Laurie, Birdie, and Chickie), recalls that Vivian was snubbed by some members of her own community. Vivian’s parents, like Laurie’s parents, lived in an affluent neighborhood in St. Louis and there was pressure not to draw attention to their daughter’s career as it was not considered to be a respectable job. Community perceptions often discouraged aspiring dancers from moving forward in the entertainment world. For example, Vivian turned down an opportunity to perform at the Cotton Club in order to finish her education and pursue a more traditional career in education.

St. Louis’s music scene was important for young performers getting their start in entertainment, but people came and went as opportunities arose. The city first emerged as a capital of Black music publishing in the early decades of the twentieth century with composers like Scott Joplin and W.C. Handy in residence. Over the years, as a major confluence of rail and riverboat travel, the city attracted traveling musicians and was home to renowned bandleaders like Charlie Creath (1890-1951). Many Missouri-born members of the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra and the Plantation Dollies ended up taking other gigs that took them to northern cities. Another motivation for leaving St. Louis was the oppressive racism and segregation. Segregation policies practiced at Club Plantation required the Black talent to enter through the back door, not touch dishware in the establishment, and politely tolerate the intimidating armed gangsters that patronized the club.

The Scarpelli’s brothers also staffed Club Plantation with mafia bodyguards who provided security for the club and its staff but also created a potentially dangerous environment for the chorines and the other Black performers:

It was an electric atmosphere and we all blended pretty well together—the wait staff, bandmembers, singers, comedians, showgirls, and the wise guys. Believe me when I tell you that we had some hold-your-breath-fine dancers back there…. All curves, seductive costumes with low cuts, small waistlines, shapely legs, grace, and smiles. Everybody had fun except when one of the wise guys would flirt too much with a tempting dancer who was the girlfriend of one of the cats. A hush would fill the room; the dice would freeze. A gun was pulled and there would be a standoff. But it always worked out and nobody was wasted in there. Thank God!

Clark Terry

As famed trumpeter Clark Terry's recollections reveal, the young/teenaged women who danced at Club Plantation, frequently found themselves in precarious situations in an atmosphere where men were usually armed and drinking. In this space, chorines could be grabbed or subjected to other inappropriate behavior from customers and other staff. Club Plantation was where Birdie, Chickie, and Laurie formed their earliest experiences in the Jazz world and despite having to navigate this complex and daunting environment, the three would continue their careers in even larger, more infamous clubs.

Laurie was the first of the three to leave Club Plantation. After being scouted and hired as a soubrette—a comedic female role often found in operas—in 1934 by producer Maceo Birch, she signed on with Kansas City’s Harlem Nite Club where she performed in their acts “Harlem Brown Skin Follies” and “The Three Lucky Sisters.” Those were tumultuous years in Kansas City. In 1934, the club was raided, and the manager arrested for liquor law violations. And in January of 1935, the club was shut down by the city after a series of three bombings that the “police said was an attempt to intimidate the owners into paying for protection from violence.” Although Harlem Nite Club eventually reopened, Laurie moved on to the Four Roses Club in 1936 to a rhythm dancing trio called the “Three Shades of Tan.” Meanwhile, Birdie and Chickie remained at Club Plantation and landed under the direction of dancer-turned-producer Joe “Ziggy” Johnson. Throughout the years, Chickie and Birdie maintained their professional relationships with Johnson; relationships that almost certainly contributed to Chickie’s and Birdie’s own successes.

Photograph of the Ensemble of Harlem Uproar House, 1937. Laurie Cathrell is standing just left of center above the seated woman.

By 1937, Laurie had left Kansas City and Chickie and Birdie left St. Louis. Laurie moved to New York and was performing at the Harlem Uproar House on 51st Street at Broadway under the direction of producer Leonard Harper. Harlem was a common destination for performers migrating northwards hoping to make a name for themselves. The borough had solidified its reputation as a Black entertainment capital in the 1920s, hence the numerous jazz clubs across the country referencing Harlem in their name. New York also provided chorines more opportunities to grow their careers into other jazz-adjacent avenues such as Broadway, films, soundies, and traveling circuits stretching from the American South to Canada looking for Harlem-tested talent.

Laurie permanently settled in New York and throughout the 1940s performed at a variety of venues in town. In the mid-1940s, she performed with the "Zanzibeauts" for the Broadway venue Café Zanzibar and as a chorine for Club Ebony in the late 1940s. Notably, in 1945 she performed on Broadway as one of the “Dancing Girls” in “John Wildberg Presents Bill Robinson in Memphis Bound: A New Musical Comedy with Avon Long.” She also toured with the Ebonettes in an Archie Savage choreographed show where she performed in a “jungle routine,” which featured chorines wearing revealing costumes that played on African stereotypes utilizing animal-prints, feathered wristbands and anklets, elaborate headpieces, and large hooped earrings. Additionally, Laurie took an interest in arts advocacy. In the late 1940s, she became a National Board member of the New York division of the Actor’s Guild Variety Artists (AGVA), an AFL-CIO affiliated labor union representing artists and stage managers in the variety field. One article suggests that she fought for dancers’ rights.

While living in Boston, life began to change quickly for Chickie. She gave birth to a daughter, Cindre Collins (later Cindre De Metlin). Cindre’s father, John De Metlin, a French Canadian in the Royal Air Force, was Chickie’s second husband. While he served, Chickie was left largely on her own to raise their daughter while also juggling a demanding schedule as a chorine. Shortly after Cindre’s birth, Chickie returned to New York with her young daughter and from 1939 through 1940, she performed at a series of venues including the New Capitol Cabaret, the Kit Kat Klub, and the Cotton Club.

Birdie’s life also changed significantly in the late 1930s. After a brief stint in 1939 at the New Capitol Cabaret with Chickie, she married her former Club Plantation colleague, Harry “Sweets” Edison, who was recruited to join the Count Basie Orchestra and quickly gained notoriety as a talented soloist. In 1940, the Edisons were living on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan, with Chickie and Cindre sharing their home as lodgers. Birdie was briefly unemployed, however, by 1941, Birdie (now billed as Birdie Edison) joined a traveling musical revue called “Tan Manhattan,” starring Avon Long. The revue performed at the Apollo and later, the Howard Theater, in Washington, D.C. This period marks the height of Birdie’s and Chickie’s fame as chorines. Both dancers were frequently mentioned in newspaper articles, reviews, gossip columns, and club advertisements.

Photograph of Harry "Sweets" Edison and Birdie Edison with unidentified couple, April 1944.

Birdie’s marriage to Sweets did not last. Although a record of their divorce could not be found, he notes in a 1993 interview with the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program that Birdie was his first wife:

I didn’t have no plans, I just had a ball. I was having a good time. Because I was living on 122nd and 7th Avenue and that was right in the heart of everything. That’s a couple of blocks from Sugar Ray Robinson’s place, right around the corner from the Apollo, Theresa Hotel, there were so many places around there.... Coleman Hawkins, he had come by and I remember the first time, I was sitting on the stoop and he said, ‘I got a gig in Cleveland, come on get in the car, get your bag and make this week with me….’ So, I went upstairs and got my horn, put a few things in a bag. And, I was married to my first wife at that time, she was a show girl, a chorus girl.

Harry "Sweets" Edison, 1993 Smithsonian Jazz Oral History

One account indicates that she and Sweets were still married as late as the mid-1940s. She continued to go by Birdie Edison, though there are very few subsequent references to her career and personal life. In 1947, she attended a birthday party for Gertrude Levy, sister of John Levy and sister-in-law of famed chorine-turned-club owner, Wilhelmina “Tondaleyo” Grey Levy. In 1948, she was one of the Club Ebony chorines, though it is unclear if she and Laurie worked at Club Ebony at the same time. Towards the end of Birdie’s career though, she crossed paths with Laurie again. Between 1950 and 1951, they worked together at Club 845 in the Bronx as part of the act Henry LeTang’s Six Sepiettes. The last reference found for Birdie indicates that she and Laurie spent the winter season performing at the Rose Room in New Jersey. Beyond the early 1950s, Birdie disappears into obscurity.

Joe Louis Funeral Program

Laurie’s dancing career drew to a close as she approached her forties. By 1953, she transitioned from chorine to barmaid, a profession that allowed her to continue working in nightclubs. She also continued her activism, serving in 1953 as Acting Vice President of the United Barmaids Association. Although very little is known about her personal life after the 1950s, Laurie spent the remainder of her life in New York, living in Upper Manhattan and later the Bronx. She died in New York on August 9, 1999.

By the spring of 1941, Chickie moved back to St. Louis and was working again at Club Plantation’s revue. The floorshow producer was Leonard Reid and Chickie had taken over as lead dancer of the chorus line. Later that year though, Chickie announced her retirement from dancing to study stenography at the Tucker Business College in St, Louis. Her decision to retire may have had to do with her new marriage, the arrival of her daughter, or perhaps she simply wanted more stability.

Her new career ambitions were cut short when in late July 1942, Chickie tragically passed away in Kansas City, Missouri. Although it was reported at the time that Chickie died of a “brief unspecified illness,” it was well known within the St. Louis community that she died from a ruptured appendix. Peggy McCullin Smith stated that Chickie knew she was unwell but was determined to travel to see famed boxer Joe Louis. She had confided to her friends that she and Louis were romantically involved. Smith added that Chickie’s friends urged her not to go, because they recognized the symptoms of appendicitis, a common condition of the time. However, Chickie did leave town and, unfortunately, died while traveling. Her funeral was a week later in St. Louis and was widely attended. One article noted that thousands of people paid their respects to the beloved chorine who was only in her late twenties when she died. Her funeral service was so well attended that it exceeded capacity. This largely reflects McCullin Smith’s recollections of Chickie as “effervescent and full of joy.” Her pallbearers included James Jeter and Hayes Pillars of the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra and the Club Plantation chorines served as honorary pallbearers. Her three-year-old daughter, Cindre, later became a talented dancer like her mother.

Like most women in their profession, Laurie’s, Birdie’s, and Chickie’s careers were rather short due to many issues including, ageism, family responsibilities, social stigma, health, and exhaustion from endless nights on the road touring and staying in substandard segregated accommodations. Though they have largely been forgotten, their jazz legacies are undeniable. Collections such as NMAAHC’s Cathrell Collection preserve the dynamic, exciting artistry of these women and their peers. Unearthing their lives is both vital to fully understanding jazz culture, as well as the mainstream acceptance of jazz as an American artform.

Written by Carrie Feldman, Museum Specialist, and Hannah Grantham, Curatorial Assistant Published on September 24, 2021