Dr. Ron Simmons passed away on May 28, 2020, just as this collection story was being posted. The National Museum of African American History and Culture dedicates this story to Dr. Simmons and hopes that it will serve as a way to remember and honor his legacy and the decades he spent advocating for and documenting the black LGBTQ+ Movement and community.

***

Posing has been an integral part of LGBTQ+ culture for decades, if not centuries.

From John Sholto Douglas, the Marquis of Queensberry’s note accusing Oscar Wilde of "posing" his sexuality in 1895; to Madonna’s “Strike a pose” at the beginning of her 1990 hit, “Vogue;” and Pray Tell’s “legendary” opening line in the intro to the FX hit show Pose: “The category is…Live…Work…Pose!,” for well over a century, posing has been a mainstay of LGBTQ+ history and culture.

Dr. Ron Simmons, perpetually behind the camera, and a tenacious activist within the black and LGBTQ+ movements since the 1970s was perfectly poised to capture LGBTQ+ people of color participating in and posing for LGBTQ+ history. In 2019, he donated what is now the Ron Simmons Photography Collection to the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). The collection serves as a tangible reminder of the contributions African Americans have made to the LGBTQ+ movement in the United States, especially since many of their narratives have been erased from mainstream LGBTQ+ history.

Marsha P. Johnson, an African American LGBTQ+ activist and self-proclaimed drag queen, is one such figure who is featured in the Ron Simmons Photography Collection. For decades, Marsha P. Johnson was someone who was virtually unknown by the average American, since the story of gay liberation and Stonewall was almost invariably retold from a white, cis, male perspective. However, recently, there has been increased focus on exhuming the role that some black and Hispanic individuals played in the Stonewall riots and the LGBTQ+ movement at large. One twenty-one-year-old patron at the 2019 Stonewall 50 and World Pride celebrations wrote the following message on his shirt: “Thank you Marsha P. Johnson, Harvey Milk, Sylvia Rivera and Stormé DeLarverie.” Nonetheless, while some activists including Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Riviera have gained recognition for their contributions in recent times, many other LGBTQ+ scholars, activists, and artists are still largely unknown.

Marsha P. Johnson (1945–1992)

Marsha P. Johnson was born in New Jersey to working-class parents. She ran away to New York City as a teenager with only fifteen dollars in her pocket. Johnson co-founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, popularly known as STAR, with fellow trans activist Sylvia Rivera and was an active member of the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACTUP). Marsha P. Johnson never used “transgender” to describe her gender identity, since the term was popularized after her death in 1992. In fact, she often referred to herself as a “transvestite”—a term many today consider offensive. While some claim that Johnson would identify as transgender today as opposed to transvestite, I use the prefix “trans” to describe Marsha, as a more inclusive nomenclature that allows for a more expansive understanding of non-binary gender identities. In 2017, trans activist Reina Gossett, produced the short fictional film Happy Birthday, Marsha! As a fantastical exhumation of “Johnson and her life in the hours before she ignited the 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York City.” Even more recently, New York City decided to honor her legacy by installing a permanent monument close to the Stonewall Inn.

Like Marsha P. Johnson, many other individuals who have made important contributions to past and present social justice movements have gone unrecognized for decades. Even worse, sometimes, they are subject to hostility and derision. For instance, in the 1970s, many black lesbians felt excluded from the mainstream (white) feminist movement because of racism, excluded from the (male-dominated) black liberation movement because of sexism, and had to contend with homophobia within both movements. Thus, they began practicing a form of politics that emphasized their identities (gender, race, class, sexuality, etc.) as a whole.

It is this “identity politics” (as it eventually became known as) of the 1970s that gave rise to intersectionality, a term popularized by Kimberlé Crenshaw. Intersectionality describes people who find themselves at the intersections of multiple marginalized identities (e.g. black + female + queer). Today, intersectionality is considered a foundational concept in several academic disciplines and has even gained traction in popular culture. However, many people are unaware of how radical black lesbians contributed to its development as a social and legal terminology.

Although mainstream society has taken a long time to give black LGBTQ+ people the recognition they deserve, black LGBTQ+ people have always celebrated their contributions among themselves. The image above shows activist Mabel Hampton receiving an award and was taken just four years before she died. Hampton was born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, on May 2, 1902, and moved to New York City after the deaths of both her mother and grandmother.

After moving to New York, she suffered various abuses at the hands of her aunt’s husband, which forced her to run away as a teenager. However, leaving home also allowed her to join New York’s burgeoning LGBTQ+ community. She became a prolific activist and is even one of the founders of the Lesbian Herstory Archives, a repository dedicated to documenting the experiences of lesbians. At a time when attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people hinged on hostility, Hampton showed that being open and proud of one’s sexual orientation is, in and of itself, a powerful mode of activism. According to fellow Herstory Archives co-founder Joan Nestle, “When she was asked, ‘Ms. Hampton, when did you come out?’ she always replied, ‘What do you mean? I was never in!’” In 1984, at the ripe age of 82, she was named Grand Marshal of the New York City Gay Pride Rally.

I have been a lesbian all my life, for eighty-two years, and I am proud of myself and my people. I would like all my people to be free in this world. Mabel Hampton at the 1984 New York City Gay Pride Rally

Presenting the award to Hampton is Barbara Smith, another integral figure within the black LGBTQ+ activist tradition. Smith, who also has an identical twin sister, Beverly, was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1946. She attended Mount Holyoke College and graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in 1969. In 1973, she co-founded the Combahee River Collective, a black feminist organizing group that borrowed its name from the Combahee River, the site of one of Harriet Tubman’s most successful raids. In 1977, the Collective published its famous Combahee River Collective Statement. In describing their objective for creating the Collective, they write that:

The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives. As Black women we see Black feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that all women of color face.

Combahee River Collective Statement

The politics that these women developed and practiced fostered a rapid increase in the number of black LGBTQ+ organizations.

Indeed, lesbians of color founded organizations that spoke to their unique interests as women. Salsa Soul Sisters: Third World Wimmin Inc., was founded in 1974, and is believed to be the oldest lesbian-of-color organization. Salsa Soul Sisters coined its name by joining “salsa,” a Spanish word, with “soul,” a word traditionally used to connote African American origins. In this way, the group effectively signaled inclusivity toward both black women and Latinas.

Sapphire Sapphos is another lesbians-of-color organization that had its genesis in the 1970s. Founded in 1979 through a meeting held by Carlyn Williams, the organization really didn’t take shape until sometime in 1980. According to Tori Graves (former Sapphire Sapphos president) in a 1984 Washington Blade article, “The name was picked because ‘we wanted first, something that would identify with women of color and, second, we wanted to be up front about being a Lesbian group.’ Sapphire, Graves said, ‘has two connotations, that of a strong, black woman figure, and of a precious gemstone. Sappho, of course, [harkens] back to the Greek poet.’ Sappho, who lived on the island of Lesbos in the seventh century B.C., was known for nurturing her relationships with other women.”

In the face of the growing AIDS epidemic, black gay men also began relying on identity politics. In 1980, a multiracial group of gay men in California founded the National Association of Black and White Men Together (NABWMT). Their objective at the time was to tackle homophobia, racism, and AIDS discrimination across racial barriers. While NABWMT was extremely successful, other black gay men found it more expedient to create organizations that spoke to their specific needs—as men that were both black and gay. In 1986, Rev. Charles Angel, a preacher, Columbia University graduate, and licensed stock exchange broker, founded Gay Men of African Descent (GMAD) along with several black gay men living in New York City. Many similar organizations began popping up around the same time.

Gay Men of African Descent

On July 16, 1986, Rev. Charles Angel, along with Tony Crusor, Cary Alan Johnson, Reggie Patterson, Len Richardson, Colin Robinson, Harold Robinson, Ali Wadud, and others, met at the relatively new Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center (LGCSC) in Manhattan to discuss the need for a support group for black gay men. Gay Men of African Descent (GMAD) was subsequently established as the first black gay organization exclusively dedicated to political activism. Their mission statement at the time affirmed that GMAD is “A support group dedicated to consciousness-raising and the development of the Lesbian and Gay community, GMAD is inclusive of African, Afro-American, Caribbean and [sic] Hispanic/Latino men of color…” On May 12, 1989, the organization’s Board voted to transition to a nonprofit corporation. Three years later, GMAD formally became a nonprofit with tax exempt status, and by 1993, hired its first paid member of staff, moving from its previous volunteer-only model. Today, GMAD is located in Brooklyn, New York, and “has hired 135 people who served over 590,000 Black men who are same-gender loving…”

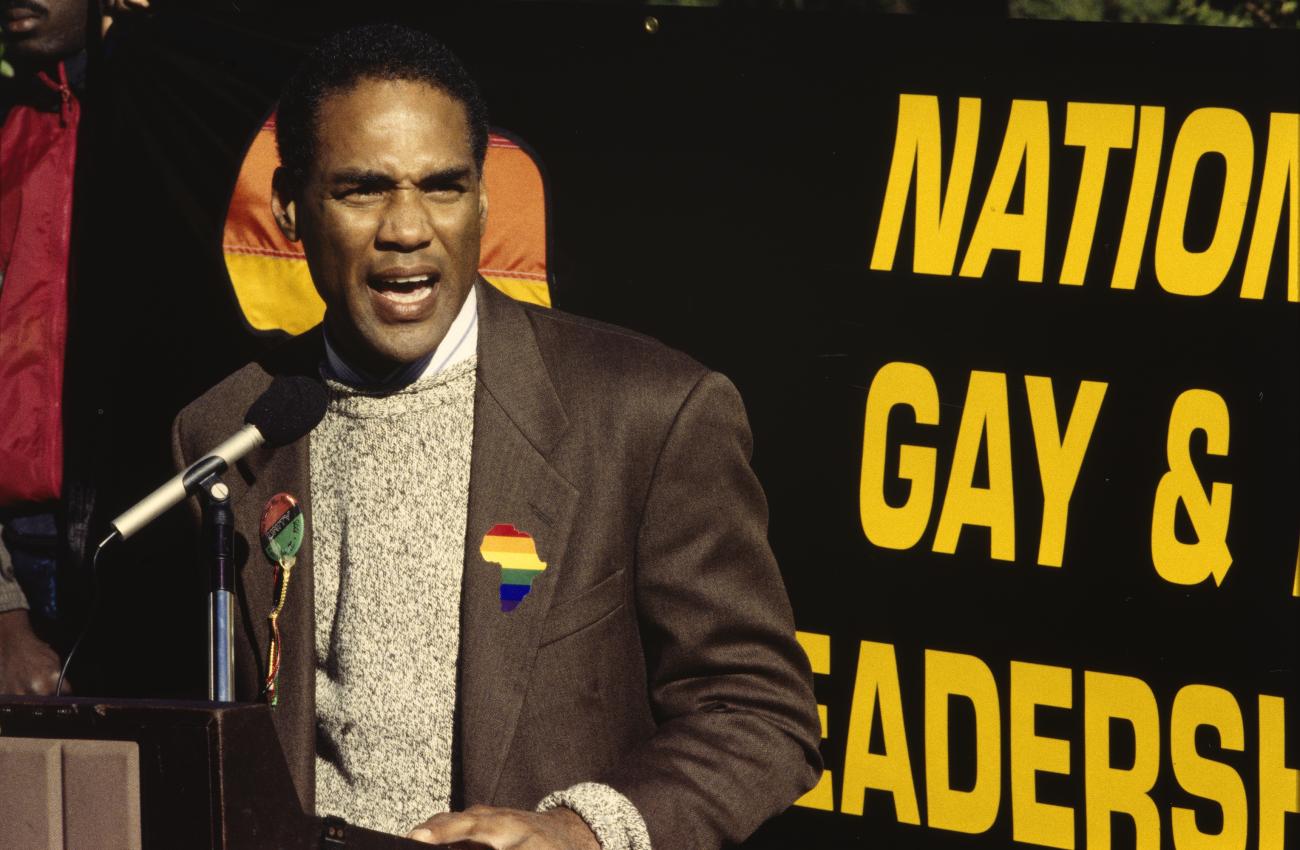

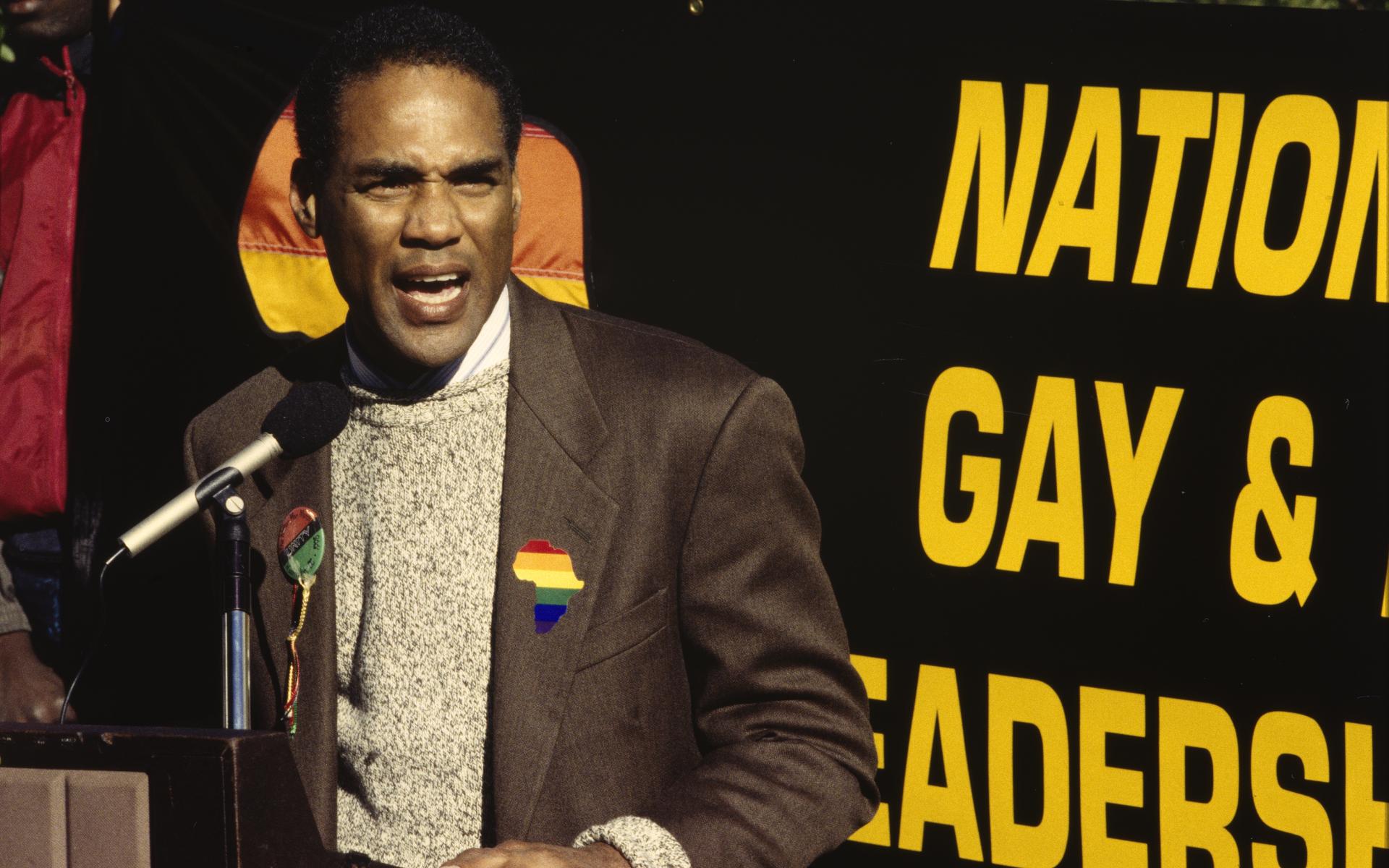

Organizing themselves into formally-recognizable groups gave black gay men the political clout and visibility that was necessary to combat issues that disproportionately affected them. But since they were also inextricably linked to both the mainstream black and mainstream LGBTQ+ liberation movements, they strategically inserted themselves in protests and marches associated with both—even when their concerns were not necessarily prioritized in those movements, and their participation possibly unwelcome. For instance, although the 1995 Million Man March, called by Nation of Islam leader, Louis Farrakhan, did not explicitly enumerate gay rights on its mission, gay activist Phil Wilson, founder of Black Gay and Lesbian Leadership Forum, seized the opportunity to call for a national group “to provide an ‘organized black gay and lesbian voice’ and ‘break the isolation’ felt by small, local and black gay groups.”

In addition to creating organizations geared toward addressing systemic oppression, black gay men created artistic circles that functioned as spaces where they could process their experiences. Some East Coast black gay men formed the BlackHeart and later the Other Countries writers collective. Like the Combahee River Collective, the name Other Countries held deep historical significance, allegedly inspired by the works of James Baldwin (possibly coming from his novel Another Country).

These black gay men also collaborated across artistic fields. Marlon Riggs, a filmmaker, used poems penned by his peers, including Donald Woods, Colin Robinson, and Essex Hemphill, for his documentaries and experimental films. Even more pointedly, he frequently referenced the slogan-turned-anthology “Brother to Brother,” and the mantra “black men loving black men is the revolutionary act” in his award-winning film, Tongues Untied. Tongues Untied was particularly salient because it confronted the fact that black gay men frequently internalized the homophobia and racism they experienced daily, making it difficult for them to see the beauty in other gay black men.

I was blind to my brother’s beauty and now I see my own, deaf to the voice that believed we were worth wanting, loving each other. Now I hear. I was mute, tongue-tied burdened by shadows and silence. Now, I speak, and my burden is lightened, lifted, free.

Marlon Riggs in "Tongues Untied"

This sentiment is one that reverberates around the black gay artistic realm. Indeed, these men made it a habit of reminding each other that they were worth loving each other. As Colin Robinson wrote in a posthumous tribute to Joseph Beam:

There’s nobody writing essays on the Black Gay Male experience, and that’s so important. Your stuff went to the heart—and there’s a new power in them for me each time I re-read them. If I had to pick your single most valuable gift, it would be the aphorism, ‘Black men loving Black men is a revolutionary act.’ And it is! As simple as it seems, it is. And that is the challenge of your life and death…And now I realize that Black men loving Black men is truly ‘an autonomous agenda…not rooted in any particular sexual, political, or class affiliation, but in our mutual survival.’

Colin Robinson, January 30, 1989You Dared Us to Dream that We are Worth Wanting Each Other

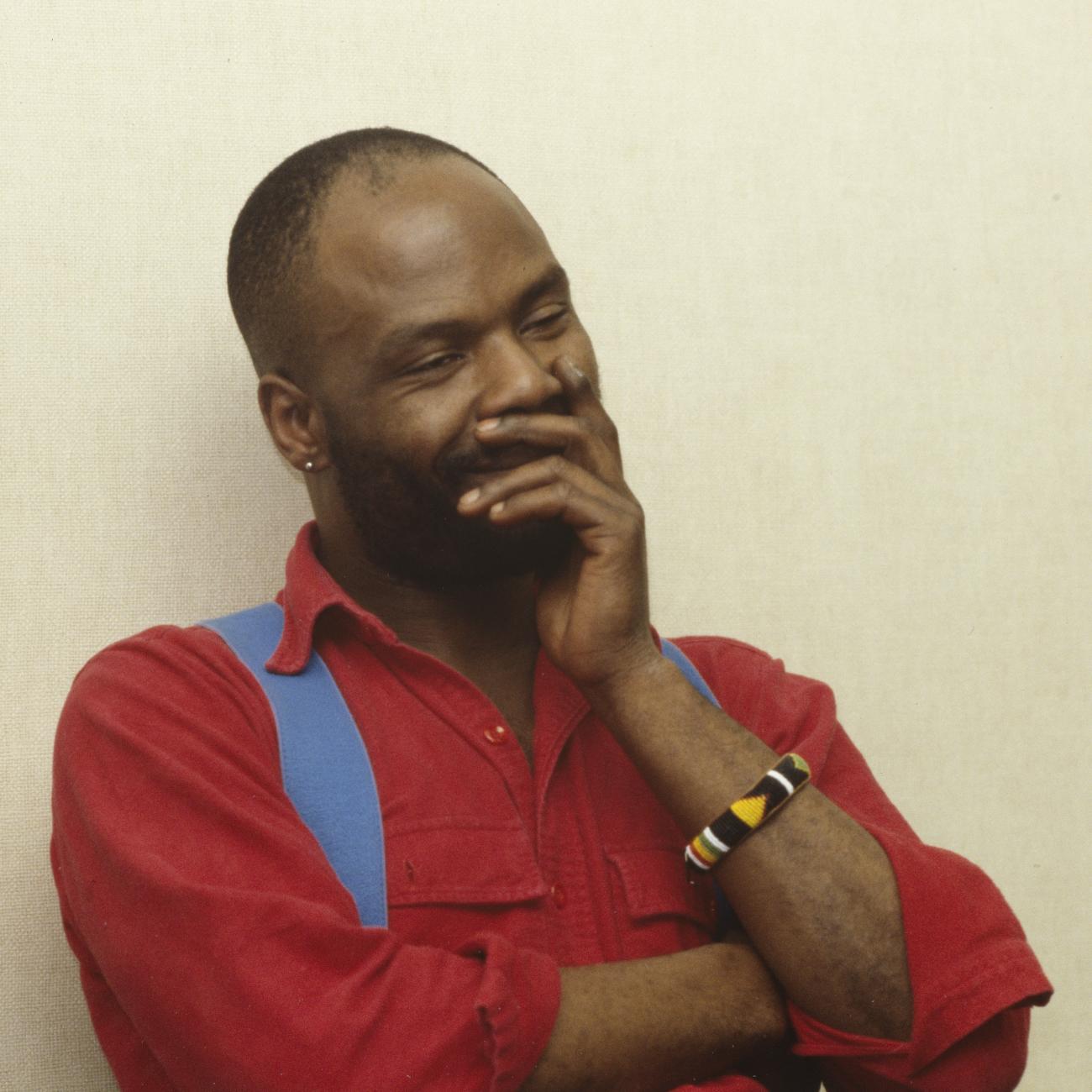

Activist Joseph F. Beam, 1985. Photograph by Ron Simmons.

Joseph F. Beam (1954–1988)

Joseph F. Beam was an African American author and activist. Beam was born in Philadelphia to Sun Beam, who worked as a bank security guard, and Dorothy Beam, a high school teacher. Dorothy obtained her high school diploma after attending evening classes while working as an adolescent. She eventually pursued both her bachelor's and master's degrees and was an employee of the Philadelphia school system for over twenty years as a teacher and guidance counselor. After attending graduate school and publishing several short stores and articles in LGBTQ+ newspapers and magazines, "Joseph began preparing and collecting materials for an anthology of writings by and about black gay men in 1982. His goal was to counteract the absence of positive images of gay men of color in the media and their exclusion from the cultural world of white gay rights activists." In addition to his black gay publications, Joseph Beam was an avid activist, occasionally giving talks and doing consultant work for LGBTQ+ organizations. In December 1988, he gave a talk at Amherst College, just a month before dying of AIDS-related complications.

The LGBTQ+ movement has made major strides since the first brick fell at Stonewall Inn more than 50 years ago. On a whole, the movement itself appears more welcoming of other identities, and the mainstream media has become significantly more inclusive of black LGBTQ+ people. Some are central characters in critically-acclaimed TV shows such as Orange is the New Black and Pose. Some are authors of New York Times bestsellers. Others are athletes at both college and professional levels.

But would this newfound inclusivity be possible without the contributions of the aforementioned individuals, many of whom were excluded from, and ridiculed by the mainstream? The Ron Simmons Photography Collection is an ever-present reminder of the valiant efforts of those who laid the foundation for LGBTQ+ liberation.

Written by Bryan Miller, Cataloger

Published on May 28, 2020

![A color photographic slide of marchers in the New York City Gay Pride Parade holding a white banner with the words [SALSA SOUL SISTERS 3RD WORLD WOMEN] printed in black.](/sites/default/files/styles/max_1300x1300/public/images/slideshow/ta2019_38_1_1_1_15_001_rotating.jpg?itok=kWeyDZxh)